I. The post-history of art

In debates regarding the history of European art, we have become accustomed to the idea of the “death of art” as its absorption into the sphere of philosophy. In any case a common platform for theoreticians, Marxist or otherwise, has been formed of the concept of creation gradually absorbed by the omnivorous development of technique. In fact the whole of contemporary art, from Impressionism to the present day, from the mid-nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century, has seemed to be a challenge thrown down by the artist to an era founded on technical reproducibility. The evolutionistic sense of the contemporary world has therefore been supported by the ideology of “linguistic Darwinism”, the fruit of an idea of the linear development of research and of a historicist view of progress. The progress of history and the progression of languages formed an objective parallel convergence with respect to an optimism of experimental production regarding society and the art it creates.

The crisis of the models of the 1970s led to a revision of all this, and in the field of art we witnessed a theoretical shift from the “evolutionary” linearity of the neo-avant-gardes to the eclectic progression of the Transavanguardia. For some people the end of great narration meant the longed-for “death of art”, absorbed by the ineluctable analytical character that undoubtedly marks the culture of technique.

The philosopher Arthur C. Danto was quick to perceive the passage of art from history to an internal post-history, which in any case preserved the existence of history and assured a happy continuous discontinuity. In his complex philosophical pragmatism, the American scholar put forward an original way of looking at art, guaranteeing its nomadic character and a special investigative spirit. However, while at first he hypothesised an “art transformed into philosophy”, he subsequently arrived at a more elaborate concept: the true form of the philosophical question regarding the nature of art has emerged through the internal development of art.

In this sense Danto has followed a line diametrically opposed to that of European thought, dominated by the historicism of Benedetto Croce and by phenomenology, which sees art as a cognitive practice and which has developed a theoretical thread that starts out from Dewey, from a philosophical pragmatism that never separates the aesthetic and the practical, creative experience and the experience of the everyday. In this sense Danto upholds the value of present-day art as the spiritual capacity to influence, through its forms, the positions of living.

In the ambit of theory, the American scholar assumes an anthropological vision according to which the creative process, as fertile metamorphosis, includes within it the proof of its own reality through form. Form is transformed over time into style, and thus becomes the visible proof of the transformation of life.

While socialist realism offered itself as an apology of existence, an organic activity compliant to the metaphysical entity constituted by ideology, Danto’s theory affirms the ambivalence of the autonomy of art and its interaction with the world that surrounds it.

Here he is not claiming any proud hegemonic value for the creative process, but is pointing rather to the capacity of aesthetic experience to have an effect on everyday experience. At the same time he points to the permanent way in which everyday experience accompanies the strategy of the artist in the complexity of a universe dominated by information technology.

Information technology inevitably tends to develop a form of anorexia, the evaporation of the consistency of the object in order to be able to broadcast reality as pure information. The process of the disappearance of the object is not imitated by art, which responds with a spirit of resistance in that it does not affirm the simple, static value of information, but the more complex value of communication. This takes place not only through linguistic elaboration, but also through the choice of subjects that highlight the “hic et nunc” of the artist is in his own context, the spiritual elaboration of highly contemporary themes such as sexuality and issues related to the body and to illness.

Thus pure information regarding news about the world is turned into a formal construct capable of influencing the collective consciousness precisely through the creative process of an art that is never static evidence, but always a metamorphosis towards the enduring. An activity that affirms a process from space into time, from the gesture towards duration.

The visibility of art is ultimately measured through the consistency of form, capable of bearing witness to the happy task of living and the passage of the temporal verticality of the present into the horizontal, albeit complex endurance of history. Post-history is a positive stratagem to defeat the destructive despair of pure present by turning it into duration.

Nietzsche pointed to the ambivalence or ambiguity of artistic creation when he stated that art, in its creative tension, also contains a desire to be destructured. This proposition leads us nicely to the complex scenarios of the work of Alfredo Pirri.

At a time like the present, when a series of theories regarding the crisis of the subject direct us towards an archaeology of the modern, Nietzsche had already realised that archaeology is the natural passage within which the artist moves and offers up his creation. So beyond certain ideologies which claim that art is able to transform and improve the world as an instrument at the service of man and of society, Nietzsche reveals the structural ambivalence of creation when, as we have seen, he underlines the other drive that accompanies every creative act.

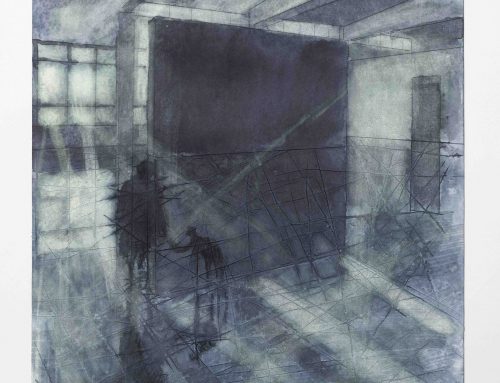

This ambivalence has been noted precisely because it throws into relief the scenario within which Pirri works and creates his own images, beginning with the history that lies around him, immortalised in archaeological finds. Pirri is attracted by the cordiality of the ruin, a trace that allows him to reconstruct an architecture with his imagination, to create a visual hypothesis of memory. Consider, for example, the rhetorical magniloquence of Roman architecture, the celebration of emptiness of space and, consequently, the sense of bewilderment that a man of our times would feel if he found himself able to view it still intact, to enter into it; or, on the contrary, the sense of cordial and thoughtful contemplation that is established when he is faced with the same architecture in fragments, in ruins, thus moving from a vertical state to a horizontal state.

The historical find has the ability to humanise the relationship with the past, allowing us to reappropriate it, to use it as ready-made, an element to be grafted in a gesture of kleptomania, absorption and entirely fantastic reconstruction.

This, then, is the artistic operation: to use the structural and philosophical archaeology of forms and genres (abstract-figurative, painting-sculpture, creation-reflection), which is not only the sign of past time, but the precise description of the landscape within which the artist moves. The aforementioned statement by Nietzsche is fundamental, because it helps us to overcome the dichotomy or the opposition that critics have attempted to create in recent years between avant-garde and transavanguardia, between the recovery of painting and other techniques, based on the belief that the avant-garde produced models that are alternatives to reality, while the transavanguardia avoided a frontal clash with history by placing itself to one side.

In reality, if we set out from Nietzsche’s axiom and admit that next to the affirmative, propositional creative drive there is also a constant desire for deconstruction, we will realise that art is a dual, rather than a one-way movement, and that it is therefore not possible to divide up the history of art, in maniacal fashion, into good artists and bad artists, revolutionaries and conservatives.

In some periods of history, such as our own, Nietzsche’s statement that the artist himself is instinctively suspicious of himself, of his parasitic, futile nature, is accepted more naturally: Pirri highlights the ethics of acting and reflecting together to reveal the uneasy conscience of the work.

II. The art of history

In Mannerism itself the destructive drive that Nietzsche identifies is found necessarily in the choice of the artist to begin his work from finds that lie around him, as the memory of the past, which he then puts together and reactivates by recycling them within an image that belongs to him. We thus arrive at Pirri’s latest work, in which this recycling is performed, but through the capacity to play with a “gentle project”, an idea of construction as the structuring of materials, though always on the basis of a balanced conscience, in which two terms remain interwoven.

It is extremely important today to understand that art is not the effect of a progress, nor a defect with respect to a lack of progress, but a sort of opulence that has accompanied us since the birth of humanity, a gap, a difference, an introduction of surprise that serves humanity to go beyond the codes of the established communication of interpersonal relations. It does not require links or homologisation with other disciplines, nor recognition at a political level, in that it has finally managed to free itself from the obsessive confrontation with the world of technique and technology, as is demonstrated by what has happened from Impressionism onwards, in relation first to photography, then to cinema, television, etc.

Until the 1970s the value of art lay in its processes, guaranteed by the identity of the artist who was linked to a political ideology. In times when the identity of the artist is also linked to his professional competence, as a producer of works, we see a return of the complex question of the quality and the value of the work, since there are no parameters capable of defining it.

Pirri’s art is characterised by the fact that it allows the obstacle of forms, starting out from a value that the result alone can determine, since it can no longer be determined in idealistic terms by objective parameters: not by the novelty of technique, but by the intensity of the work, in other words its ability to spark off energy, difference and surprise, the powerful, catastrophic ability of art to enter the scenario of our images and to turn them upside-down.

III. Pirri’s victory

The contemporary relevance of Alfredo Pirri lies in the powerful presence of a body of work that has succeeded in finding a balance between the creative process and the formal result. Art that tends towards the dematerialisation of the object has generally favoured the moment of planning rather than that of execution. Pirri, however, has always worked in the dual direction of the concept and the object that emanates from it.

The value of the project undoubtedly assumes decisive weight in Pirri’s linguistic strategy, in that it is the bearer of special articulations of the material devised by the artist. He decides on an initial form which gradually develops through modular moments that multiply the starting moment.

The module becomes the structural element that founds the possibility of form, always based around the complexity that multiplies the surprise of geometry, potentially ad infinitum. Conventionally, geometry seems to be the field of pure evidence and of inert demonstration, the place of a mechanical and purely functional rationality. In this sense it seems to favour the premise, in that the conclusion becomes the inevitable outcome of a deductive and simply logical process.

Pirri, on the other hand, has founded a different use of geometry, as the prolific field of an irregular reason that develops its own principles asymmetrically, adopting surprise and emotion. These two elements are not, however, contradictory to the principle of the project: if anything they reinforce it through a pragmatic, rather than preventive use of descriptive geometry.

It is no coincidence that the artist moves continually from the two-dimensional nature of the project to the three-dimensional execution of the form, from the black and white of the idea to the polychromatic articulation.

This proves that the idea generates a creative process that is not purely demonstrative, but fecundating and fecund. In fact the final form, two-dimensional or three-dimensional, presents a visual reality that is not abstract but concrete, pulsating under the analytic and moving gaze of the spectator. The principle of an asymmetric reason underpins the work of Pirri, who formalises irregularity as a creative principle. In this sense form does not end in the idea, in that there is no cold specularity between project and execution. The work brings with it the possibility of an asymmetry accepted and assimilated in the project, in that it participates in the mentality of modern art and of the conception of the world that surrounds us, made up of unexpected events and surprises.

Pirri’s classical quality lies precisely in this, in having accepted happily the intelligent chance of life, the openness of the universe. Art becomes the place where the artist formalises these principles, incorporating them in the work characterised by a geometry based on asymmetry that produces something that is dynamic rather than static. Pirri, in fact, always creates families of works, in that they are derived from matrixes which can be used to produce complementary and different forms.

In this way the concept of project comes to assume a new meaning, for it no longer suggests a moment of brilliant precision, but of open experiment, albeit guided by a method constructed through practice and execution. The method naturally involves a need for a constant, progressive parameter, anchored to a historical awareness of the context dominated by the principle of technique.

Technology develops productive processes that are based on standardisation, objectivity and neutrality. The constituent principles of a creativity different from that built on the traditional hyper-subjective idea of difference. This emptying is not seen by Pirri as a loss, as it might seem from a late humanistic or Marxist point of view. In reality it becomes the result of a new anthropology of man that works according to a metabolism of modular reason, which does not mean symmetrical repetition but asymmetrical multiplication, the application, that is, of the new rules of intelligent chance as opposed to indistinct chaos. Intelligent chance means the ability of man to accept discontinuity without falling into the despair of a hopeless rationality. The acceptance is born of the loss of conceit on the part of Western logocentrism, which absorbs the patient analytical spirit of the Oriental world and moves pragmatically not on the warpath but with a sense of openness towards the world.

This is what Pirri does as, in his own way, he constructs his monuments to the contemporary world. There are many similarities, as well as many differences, between his work and that of Tatlin, who produced his monument to the Third International. In both there is a faith in the ethical reason of art, capable of creating artistic forms that suit their times. The difference lies in the notion of Utopia used by the two artists, one a Russian working during the Soviet Revolution, and the other an Italian working later.

In Tatlin there prevails a concept of positive Utopia, present in all the historical avant-garde movements of the twentieth century. The idea, that is, of the power of art and its language, its ability to impose its own order on the disorder of the world. The optimism of reason in its own ability to affect the process of transformation of the world and of social behaviour.

In Pirri, as in other European and American artists of the post-war period, there emerges a concept of healthy negative Utopia, understood as the awareness of the fact that it is impossible for art to establish an order outside its own confines. In some way the ethic of action prevails over the politics of creation. An ethic which in any case identifies a process of focusing of the projectual and executive procedure of art.

Pirri, in fact, plans his forms alone, and then sometimes delegates their execution. This does not mean an abandonment of the product or the conceit of the artist who attaches more importance to the planning phase than to the executive phase. If anything, it points to the possibility of art to open up an exchange and a contact with society, eliminating the conventional ritual of invention, the religious mystery of the realisation of the work that has accompanied much contemporary art. The asymmetry also involves the principle of collaboration and collective contact.

There are no figures here, but installations, sculptures and other geometrical forms redolent of mythology, which constitute the figurative in an age accustomed to technology and its tendency towards the dematerialisation and abstraction of bodies. Art, on the other hand, tends to make forms evident, to turn even geometry into bodies. Pirri’s two- or three-dimensional forms, in fact, are always concrete linguistic realities, the affirmations of a mental order that is never repressive and closed, but always fertile and unpredictable. In any case the forms germinate and multiply with sudden unexpected angles that reveal the possibilities of a new geometrical eroticism. These forms always display a domestic monumentality, far from the overbearing power or the rhetoric of sculpture. This means he does not want to produce a conventional war on the existing forms of reality, but to realise a linguistic field of analysis and synthesis. The analysis is produced by the possibility of verification of the germination of these families of forms, the synthesis by the delicate power of the overall picture that unfolds before our eyes.

The works of Pirri are pyramids of art, places of convergence where it is possible to think and to act, where the project and the realisation are woven together concretely to create a system that produces not only forms but also social behaviours. This is Pirri’s victory. A true victory. That of art. Because one’s name is one’s destiny. And his name is Pirri, not Pyrrhus.

Achille Bonito Oliva

Translated from Italian by Mark Eaton